Digital Initiative Exposes Structural Flaws in Electronic Voting Systems

The RMN microsite argues that when domestic accountability mechanisms fail, international technical observation and comparative oversight may become necessary.

By Rakesh Raman

New Delhi | January 30, 2026

As governments worldwide accelerate the digitisation of civic infrastructure, electronic voting machines (EVMs) have increasingly been presented as symbols of efficiency, scale, and technological progress. Yet, the integrity of any digital system depends not merely on speed or convenience, but on transparency, auditability, and public trust.

A long-running digital initiative by Raman Media Network (RMN) and RMN Foundation—“EVMs in Indian Elections: Threat to Democracy”—has emerged as a rare, sustained attempt to examine whether India’s electronic voting architecture meets these foundational criteria.

A Digital Microsite Built for Public Scrutiny

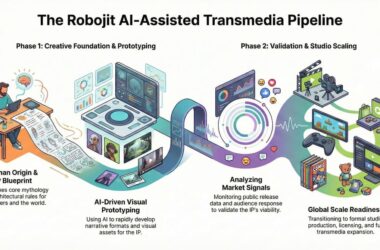

Launched nearly five years ago as a Canva-based microsite, the project functions as a public-facing knowledge repository rather than a conventional campaign platform. It aggregates technical critiques, legal challenges, citizen testimonies, parliamentary debates, and independent research related to the use of EVMs and Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) systems in Indian elections.

Unlike official portals, which typically assert system reliability without enabling independent verification, the RMN microsite adopts an open-documentation approach. It curates publicly available data, media reports, videos of street protests, expert analyses, and opinion polls to allow readers to examine patterns and inconsistencies for themselves.

The Core Digital Question: Verifiability

At the heart of the debate lies a fundamental principle of digital systems design: verifiability.

India’s Election Commission maintains that EVMs may occasionally malfunction but cannot be tampered with to alter results. Critics, however, argue that such assurances lack credibility in the absence of transparent, end-to-end audits accessible to independent observers.

The microsite highlights concerns around VVPAT systems—introduced to provide paper-based verification—where the paper slip is briefly displayed to the voter but not meaningfully reconciled with final electronic tallies. Technologists and election observers cited in the archive question whether a verification mechanism that is neither fully counted nor independently audited can serve its intended purpose.

Ignored Complaints and Institutional Silence

One of the most striking patterns documented by the initiative is the volume of unresolved complaints. Opposition political parties, civil society groups, and individual citizens have repeatedly raised concerns about EVM behaviour, statistical anomalies, and constituency-level irregularities.

Yet, according to material compiled on the microsite, India’s key democratic institutions—including the Election Commission and the Supreme Court—have shown sustained reluctance to order comprehensive technical audits or halt EVM usage pending independent review. From a digital governance perspective, such institutional opacity undermines system credibility, regardless of whether manipulation is ultimately proven.

Comparative Global Perspectives

The microsite situates India’s experience within a broader international context. It references global debates on electronic voting, including statements by political leaders such as US President Donald Trump, who has publicly advocated a return to paper ballots citing security concerns.

It also draws attention to findings by the Citizens’ Commission on Elections, which documented multiple anomalies associated with EVMs and VVPATs, and to international best practices that prioritise physical audit trails, open-source software, and multi-layered verification.

A frequently cited quote by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan frames the issue succinctly:

“Building democracy is a complex process. Elections are only a starting point, but if their integrity is compromised, so is the legitimacy of democracy.”

Technology Without Oversight Is a Risk Multiplier

From a digital systems standpoint, the controversy surrounding EVMs underscores a broader lesson: scale amplifies risk when oversight is weak. India conducts the world’s largest elections, and any systemic vulnerability—technical or institutional—has consequences that extend far beyond national borders.

The RMN microsite argues that when domestic accountability mechanisms fail, international technical observation and comparative oversight may become necessary. It calls for structured engagement with global parliamentary and democratic institutions, including the Switzerland-based Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), to assess electoral technologies against international norms.

A Case Study in Digital Accountability

Rather than claiming definitive proof of election manipulation, the initiative positions itself as a case study in digital accountability. It raises uncomfortable but necessary questions:

Who audits critical civic technologies?

Who verifies the verifiers?

And how does democracy function when citizens are asked to trust systems they are not allowed to examine?

In an era where algorithms increasingly mediate public life—from banking to welfare to elections—the answers to these questions will define the credibility of digital democracy itself.

EVM Microsite: https://rmnsite.my.canva.site/evm-website-rmn

By Rakesh Raman, who is a national award-winning journalist and social activist. He is the founder of a humanitarian organization RMN Foundation which is working in diverse areas to help the disadvantaged and distressed people in the society.